The fortunate fluke of the Barossa Valley was the geological down throw of the Stockwell fault that created the fertile valley which traps the water while cold air drops in from the surrounding hills. The Barossa Valley is also just at the limit of clouds bringing in moisture before the rain-shadow begins. Further east and north the land dries off before dropping down into the arid lands of the vast Murray Basin.

There can be little doubt that the flavours of the magic three – shiraz, grenache and mataro – equal the best globally. We are blessed as consumers though Australians, as is our way, are a bit grudging in appreciating riches that allow us to drink the ‘best of the best’ for modest prices on a daily basis.

General Information About the Barossa Valley

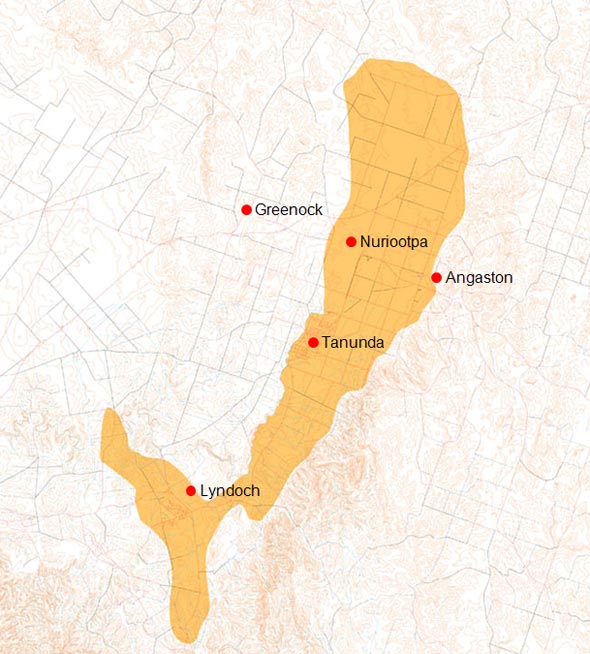

The Barossa Valley is a north east trending valley extending about 36 kilometres from Williamstown at the southern end of the Lyndoch Valley to St. Kitts Creek which closes off the northern end of the Barossa Valley. It is bounded by two ranges referred to here as the Western Ridge which is part of the North Mount Lofty Ranges and the Eastern Range which is part of the South Mount Lofty Ranges. The southern extension of the Eastern Range is also known as the Barossa Range.

The ‘flat lying’ part of the Barossa Valley varies from 2 (Lyndoch Valley) to 5 kilometres in width. Along both sides, the slopes into the Valley are covered with vines. Along the eastern edge this is mostly a simple slope off the Eastern Range. Along the Western Ridge vines are planted many kilometres back into the slopes of the Range and often in well defined separate valleys such as Seppeltsfield. Including these vineyards the width of the Barossa Valley swells to 12 to 14 kilometres at its widest. The greatest density of vines is however along the spine of the Valley floor.

A Highlight Summary of the Barossa Landscape

1. Many of the worlds wine regions have developed on sediments that have a recent origin and were created by the melting of ice sheets that began about 18,000 years ago. Most are dated at less than 12,000 years old. Some of the vineyards of Argentine, Chile, New Zealand, and Oregon-Washington are examples. Many other European, New Zealand, and South American vineyards grow on landscapes that are younger than 300,000 years with the main vineyards of Bordeaux being on terraces about 1,000,000 years old.

2. The Barossa Valley is unusual because of the great age of the land surfaces, some of which can be traced back to 200 million years ago.

3. The great age of the Barossa Valley has allowed numerous land surfaces to develop on a wide variety of underlying rocks and sediments dating from 200 million years to the present.

4. The Valley part of the Barossa Valley began 35 million years ago and this Valley was filled over the next 30 million years with a tiny sequence of sediments carried in by streams from the surrounding low relief landscape.

5. On average the Valley filled with less than 100 metres of sediment giving a rate of deposition of one millimetre per 30 years.

6. The landscape of the Barossa Valley today with the major feature being the Eastern Range has been created in the last 5 million years.

7. The land surface of the Barossa Valley can be divided into 13 separate sub-regions with vineyards planted on 12 of these. These may or may not coincide with sub-regions that wine makers recognise as producing different tastes.

8. The idea of sub-regionality while not new is gaining pace with many wineries referring to single vineyard sites and local district names.

A comprehensive paper on History of the Barossa Valley and Its Landscapes was presented by at the Wine Barossa media and trade Day, June 18th, 2008. It can be downloaded at download doc (7,145 kb)

See HERE for details of other South Australian wine regions