Wednesday, 19th May, 2010 – David Farmer

Soil rocks and wine. The chemistry of what the vine grows in adds little if anything to the taste of wine. That’s the conclusion my studies had led me to.

Wine does not show a taste that can be related back to primary or secondary minerals in the soils and weathered rocks. The soils and rocks do though have an important bearing on how necessary nutrients are taken up by the vines and most specifically how the vine gains access to water. This does affect the taste in a major way.

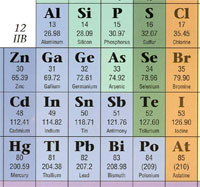

Many others see this differently. Two reports over the last year or so need to be recorded as they may suggest my view is wrong. In January, 2009, researchers, Alex Martin and John Watling, from the University of WA reported that they created a fingerprint for 400 wines from around Australia. To do this they used mass spectrometry and recorded the concentration of 60 trace elements.

They showed that each region had a specific fingerprint from the concentrations of these trace elements. Thus wines made from one variety in one region are different in trace element composition to the same variety in another region. Using this method they hope to be able to identify where the grapes were grown in a wine. Presumably from wines made from a confined region versus a multi-district blend the origins of which I imagine would be too hard to unravel.

This raises several interesting thoughts. It is likely that trace elements vary for wine region to wine region as the soils and rocks do have a lot of variability. Why though would a vine take up more than was required of any element just because it was more abundant? If say the trace element selenium varies from region to region why would vines take up more than needed, assuming of course that these trace elements are playing some active role and are not just sucked up and have no real end use. This study though says that indeed is what the vine and presumably other plants do.

Also while some Australian regions have remarkably uniform soils and sub-soil rocks, e.g. Coonawarra, others like the Barossa show great diversity. While I can understand a fingerprint for Coonawarra I have trouble seeing how the Barossa cannot but have dozens of fingerprints.

Now the variation of these concentrations of trace elements will not be detected by us in the aroma or taste of a wine, because our powers of detection are too coarse. It follows that perhaps other soil or rock chemicals could also be sucked up and these might vary in concentrations, from region to region, by an amount we can detect. In this way they reflect the soils and rocks and you would then legitimately say about a wine that for example it has a flinty taste because of these special soils and rocks.

Similarly scientists led by Regis Gougeon, from the University of Bourgogne, in Dijon, France, using a mass spectrometer also reported (June 2009) that they can tell the grape variety, the district of origin of the grapes and even the type of oak used to mature the wine.

“Our approach reveals the extremely high yet unknown chemical diversity of wine. It was exciting to be able to observe such a diversity at once, where many compounds, even in low concentration, may contribute to the body of the wine.”

The story goes on to say; ‘The flavour and aroma of a wine is influenced by a range of factors from the grapes used, the soil they were grown in, the climate at the time, the yeasts that aided the fermenting process and the wood used to make the barrels the wine was aged in.’

Taste Depends on the Variety

This French study, and numerous others for that matter e.g. AWRI, confirms what we know as drinkers which is the taste of wine depends on the variety and where it is grown and a large part of this taste comes from the climate. Mass spectrometry being objective and far more sensitive than humans is quickly providing lots of the answers as to which chemicals make the aromas and tastes we like.

But we are still not at a point where we can say of a wine; when the vines are grown on soils or rocks of this type, in this climate, this chemical is produced in greater quantities and can be identified in the taste. The linkage that the taste comes from a higher concentration of specific elements that are only found in particular soils and rocks eludes us.

That is why the University of WA study is interesting as it is about trace elements some of which while rare will have higher concentrations in some rocks and soils. It does not seem to me that this will relate to tastes but if studies like this can show a vine will concentrate elements because of the ‘geology’ I may have to rethink my idea of the role of soils and rocks. Still I would then want a plant physiologist to explain to me why a vine would want to concentrate more of an element than it normally needed just because more was available.