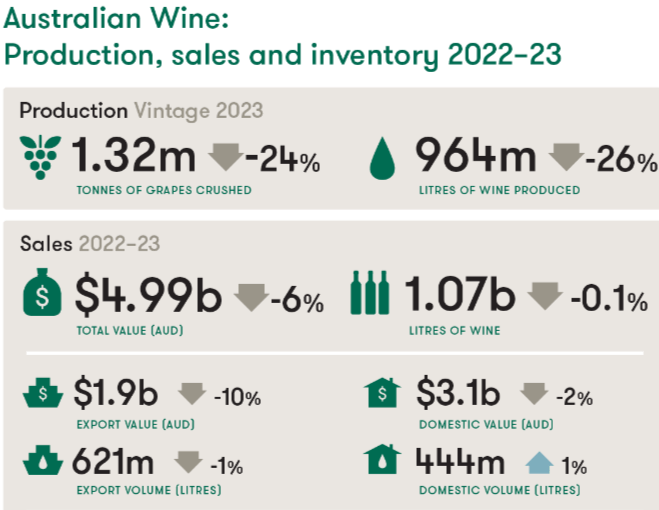

Australia’s wine industry is at a crisis point after a lost decade that sees both exports and consumption at home declining. And the continuing impact of a cultural cringe makes the shrinking hard to end.

The idea that European ideas define what good wine should be like is embedded in our key influencers.

Wine show judges and critics alike extol the virtues of cooler climates. That’s what the highly rated wines of France and Germany are made in so it must be what Australia needs for greatness.

Cabernets and pinots are the noble grapes of Bordeaux and Burgundy so shiraz can be nothing but a colonial upstart.

And then there’s the real cultural cringe word – terroir, derived from the Latin word terra meaning earth or land. It’s used by the French to express “a wine’s sense of place” and the special character a wine is thought to get from the particular place where the grapes were grown to make it.

Australia’s self proclaimed experts have embraced the word as a key to determining what wines are good. To qualify there needs to be a place of origin -a label attaching a geographical indicator. Preferably somewhere than can be described as having a cool climate.

Miniscule producers Yarra Valley, Mornington Peninsular and Tasmania are favourites. Margaret River qualifies despite grape growing temperatures not really being much lower than those at McLaren Vale.

A special dispensation for heat is given to the Hunter Valley, probably beause of the bias inherent from Sydney’s long dominance of the wine commentariat who dare not knock Hunter semillons.

Wines from Clare and the Adelaide Hills are far likelier to get the top wine show gongs than their Barossa Valley neigbour. And don’t dare mention fine wine and the Murray Basin in the same breath unless you let botrytis under a hot sun make a real sweetie.*

Yet we only have to look at Penfolds to see that the wines the market rewards as Australia’s finest owe nothing to being from one of the noble grapes, nor having an individual sense of place, nor the “advantage” of growth in a cool climate.

Three examples:

Grange 2019 – Shiraz (97%), Cabernet Sauvignon (3%) from Barossa Valley, McLaren Vale, Coonawarra, Clare Valley

Bin 28 Shiraz – described by Penfolds as a showcase of warm climate Australian shiraz – ripe, robust and generously flavoured with the current 2021 vintage a blend of wines from McLaren Vale, Barossa Valley, Padthaway, Wrattonbully, Clare Valley.

Bin 389 2021 – Cabernet sauvignon (53%), Shiraz (47%) with fruit from McLaren Vale, Coonawarra, Barossa Valley, Wrattonbully, Padthaway.

Warm climate multi-regional blends are Australia’s unique contribution to the great wines of the world. Surely they should be at the forefront of promotional efforts by Wine Australia and others.

That they are not I put down largely to the cultural cringe that was a hallmark of my generation (at 81 I am too old to be a Boomer – I think they call us the Post War generation). Drinking table wines was a new thing for us and with that, as with so many things, it was to the “old world” we looked for guidance.

And we found Michael Broadbent at the auctioneers Christies promoting to us his finds in the great houses of England and Scotland of long cellared first growths. It all made such a romantic story to add a little majesty to the adventure of wine discovery.

Bordeaux and Burgundies were the benchmarks which Australia’s nascent wine revival of the ’60s and ’70s could only aspire to reach. The French classics with their terroir became the measuring stick which that gifted wine lover and promoter Len Evans instilled into other enthusiasts.

The gospel of noble varieties grown in cool climates grew and grew with would-be wine judges selected from the tasting schools set up by Len and his disciples. It became a self fulfilling prophecy.

There was a brief challenge to this Australian wine industry orthodoxy when Robert Parker with his Wine Advocate was extolling the virtues of wines from riper grapes that led to a growth of Barossa exports to the United States.

Australian wine judges repulsed the alien influence as James Halliday joyfully recordered in a 2005 Wine Press Club of NSW Annual Lecture. He commented: “Many of these small producer wines [from the Barossa] are fairly and squarely aimed at the Parker palate, tipping the scales at 15% to 16%, massively fruity, massively structured, and swathed in oak. The near-absence of Barossa Valley trophies is explained by two factors: most do not enter the show system, and those that do, have negligible success. It is, if you like, a simultaneous poke in the eye for Messrs Parker and Kramer [of the Wine Spectator] alike.”

*Maybe fortified muscats from Rutherglen can be called another exception to the cool climates are best dogma.