By Professor Jane Golley and Professor James Laurenceson

With the Australian economy weathering the disruptive trade measures Beijing imposed in 2020, much triumphalism has followed. As one commentator put it, “While they hurt for a while, Australia found other markets.”

Tell that to the wine industry. After putting years of investment and hard work into product development, marketing, and logistics, by early 2020 a high value-added, non-resources export industry showcase had been created, worth an annual $A2.9 billion.

In November 2020, Beijing imposed tariffs ranging from 116.2 percent to 201.8 percent, alleging its domestic industry was being harmed by Australian wine being dumped in the Chinese market and that it had benefited from unfair subsidies.

Now, three years later, Australia’s wine exports are down by a massive $A975 million. A $A1.1billion collapse in sales to China has only been offset by increased deliveries elsewhere worth $A161 million.

So no, the wine industry’s experience is not that Australia has “found other markets.” And the measures imposed are still hurting.

The temptation is to blame the industry itself for recklessly accumulating a large exposure to a single market. The share of Australia’s wine exports going to China rose from 12.2 percent in March 2014 to 39.9 percent six years later. But this would be a lazy assessment, not an accurate one.

By the end of 2019, the global market for imported bottled wine was worth $US25.8 billion. It was also essentially stagnant, up by just $US355 million since 2014. One market stood above all others in offering both scale and growth: China. Whereas Chinese imports jumped by $US826 million between 2014 and 2019, other markets fell by a collective $US470 million.

No surprise then that it was China delivering 85 percent of the growth in Australian exports during this period. Far from being reckless, Australian wine producers were simply following market opportunities. That’s Business 101. For smaller, family-owned vineyards, the China market was truly unique. Between March 2014 and March 2020, the number of Australian wine exporters selling to China rose from 900 to 2,347. In March 2023, there were only 111 remaining.

Pursuing market diversification requires investing scarce resources in multiple markets, each with uncertain returns. This risk management strategy might be feasible for an industry major like Treasury Wine Estates (TWE). It has diversified some of its sales away from China towards Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, while also launching a Chinese-made offering, “One by Penfolds,” at around $A50 per bottle.

But these moves will never be practical options for producers of more modest means. They live (and die) by their access to the China market.

Economist Tim Harcourt recalls how South Australian wine exporter Pip Crawford had created a thriving business that focused on the second-tier Chinese city of Qingdao, rather than compete head-to-head with the industry giants in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. Reflecting on Crawford’s diversification options, Harcourt mused: “How could the [Australia] government tell her to walk away from that lucrative contract and go somewhere else? She wouldn’t be keen to switch cities, let alone countries.”

Other anecdotes alluding to the human cost abound.

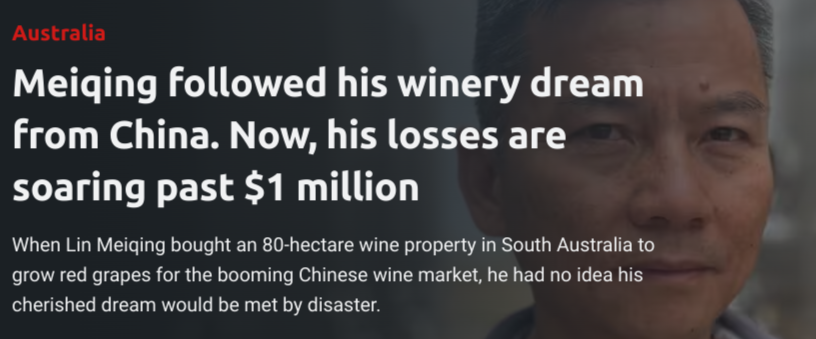

Lin Meiqin was a successful importer of Australian red wine to China in his home province, Fujian, before migrating to Australia in 2012 and buying a Riverland vineyard (Sky Road Wine Estate) in 2015. Riding the red wine China boom, Riverland output peaked at two million bottles of red wine, all shipped to China. He is expecting zero income from the vineyard this year.

Likewise, Nikki Palun started exporting wine to China in 2014, peaking at over two million bottles a year (90 percent of total sales). With the tariffs, her export business has “disappeared” because “nothing can replace China in terms of volume.” Making this predicament worse is her sense that the tariffs were not inevitable: “the problem was not China but a lack of skillful diplomacy by Australia’s previous government.”

The dire current state of the Australian wine industry is also notwithstanding geopolitical friends declaring they would step up to help out.

The month after Beijing imposed tariffs, the Inter-parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC) – self-described as an “international cross-party group of legislators working towards reform on how democratic countries approach China” – launched a “global campaign” in which, complete with Chinese subtitles, members voiced the merits of their own speciality alcoholic beverages – “nothing beats a glass of New Zealand pinot,” “two words: Napa Valley,” “Japanese sake is the best,” and so on – before urging compatriots to follow their example and drink Australian wine “next month” because the tariffs were an “attack on free countries everywhere.”

Four months after the wine tariffs were imposed, Kurt Campbell, President Joe Biden’s “Asia tsar,” delivered an “exclusive” to Peter Hartcher of the Sydney Morning Herald insisting that the U.S. was “not going to leave Australia alone on the field.”

Comfort was clearly taken by Trade Minister Dan Tehan, who a few days later reflected, “I think all Australians should be reassured by the fact that the Americans have come out and said that they’ve got our back.”

But the notion that “shared values” might provide a collective defense for Australia’s wine industry fell flat. Comparing 2022 trade data with that from 2019 shows that U.S. imports of Australian bottled wine fell by $US31 million, the largest drop of any country. Meanwhile, China’s imports of U.S. bottled wine rose by $US11 million.

The customs territories increasing their purchases of the Australian product the most were an eclectic grouping led by Hong Kong ($US33 million), followed by the U.K. ($30 million), Thailand ($US27 million), Malaysia ($US22 million), and Singapore ($US19 million). In contrast, Canada, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy – all represented in IPAC – recorded falling purchases.

In retrospect, the IPAC video might have been more effective as an advertisement for the alcoholic beverages produced by Australia’s competitors – because geopolitical friends or not, when it comes to the operation of private companies from democratic countries in global markets, that’s what they are.

The wine industry sheds light on the diverse array of experiences within just one of the sectors that has been disrupted by Beijing in recent years. Just as there is no simple narrative as to why these disruptions occurred, the triumphant narrative that all is well belies a more complex picture.

Meanwhile, those calling for the Australian government to embrace the concept of “trusted trade” with “like-minded” friends assume those friends will be there when we need them. The facts suggest otherwise.

Instead, dedicated diplomacy, as seen in the recent “barley solution,” is needed to advance the interests of Australian companies trading with China and elsewhere in this competitive, globalised world.

Trade Minister Don Farrell says he expects the same approach might later be applied to resolve the wine dispute as well. During his trip to Beijing last week, he extended an invitation to the Chinese commerce minister to visit his family’s vineyard. That won’t solve all the industry’s woes. But nor should the signal it sends be underestimated.

Professor Jane Golley is an economist specialising on China in the Arndt-Corden Department of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy at The Australian National University (ANU). She is currently an Executive Member of the Australia-China Business Council (ACT) and an Advisory Board member for the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology, Sydney.

Professor James Laurenceson is an economist and Director of the Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI) at the University of Technology, Sydney. He has previously held academic appointments at the University of Queensland (Australia), Shandong University (China), and Shimonoseki City University (Japan). His research has been published in leading scholarly journals including China Economic Review and China Economic Journal.

This article is published under a Creative Commons License from the Australian Institute of International Affairs website.